December 27, 2019

Chief Investment Officer

Newly elected Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear has released a financial analysis of a 2017 pension reform proposal that his predecessor Matt Bevin had commissioned and then kept hidden from the public. What the report shows will not be welcome news to those who claim defined contribution plans are the answer to saving struggling retirement systems.

“The proposed 2017 reforms would have cost the state more and forced out many more career employees,” Gov. Beshear said in statement when he made the analysis public last week.

According to the 65-page report, Bevin’s pension overhaul plan would have saved Kentucky money in the short term, but over the long term it would have cost state taxpayers more money while providing fewer benefits for retirees.

“It is unlikely that most of the potential savings will be realized as it is likely the system will experience an increase in the number of retirements when a member becomes first eligible for an unreduced benefit,” said the analysis, “as the new provisions provide a large economic incentive for the member to retire at first eligibility and seek other employment.”

One of the key aspects of Bevin’s pension reform plan was moving new employees in the Kentucky Retirement Systems into defined contribution plans instead of leaving them in the hybrid pension plan that was established in 2013. But the analysis said that the defined contribution plan would have been more expensive and cost 4% of employees’ salaries rather than the 3% with the hybrid plan.

The Kentucky Center for Economic Policy (KCEP) said “benefits for new employees had already been cut so substantially that there was simply no room to save money from additional cuts, and this shift actually increased costs.”

The report also said that closing the existing plan to new employees would have been costly over the long term because the plan would continue to pay benefits to retired members for many years but would have fewer employees paying into it.

“It is reasonable to conclude that the employer contributions will need to increase to offset the lost earnings,” said the report.

The actuarial analysis estimated that the eventual expected rates of returns in closed plans would have to be between 3.75% and 4.5% rather than the plans’ current assumed rates of 5.25% to 6.25%. It also said that it would have resulted in additional costs of $5 million to $11 million per year over the next 30 years.

Even though the analysis had been commissioned by Bevin when he was governor, he had blocked it from being made public. In 2017, Ellen Suetholz, a former state government attorney and member of the Kentucky Public Pension Coalition, submitted a request that the analysis be made public. But Matthew Kuhn, deputy general counsel for the office of the governor, denied the request saying that the analysis was just a draft and therefore not subject to the state’s Open Records Act.

Beshear, who was Kentucky’s attorney general at the time, found that the denial violated the Kentucky Open Records Act, a decision that was upheld in circuit court. Bevin sought and received a stay from the Kentucky Court of Appeals, which kept the analysis from being made public until it was released last week by Beshear.

“No amount of lipstick was going to make this pig attractive,” Jim Carroll, president of Kentucky Government Retirees, said in a Tweet. “Did Bevin think we didn’t know that closing down a DB plan incurs costs? Did he think we were stupid?”

December 20, 2019

Casper Star-Tribune

Veronica Kay Garcia wrote in the Star-Tribune’s Dec. 7 Forum: “Pension inflation adjustment for retirees of the state of Wyoming is long overdue.” She makes several relevant points regarding Wyoming retirees. One point in particular is that there hasn’t been an inflation adjustment for 12 years. For your information, 107 is the age of our oldest retiree; 14 retirees are over the age of 100; 679 retirees are over the age of 90. 1970 was the retirement year of our longest paid retiree.

The WREP (Wyoming Retirement Educational Personnel organization) has been pushing for an inflation adjustment for the past several years, along with the state coalition of groups whose employees receive pensions from the WRS. The last legislature, 2019, we supported House Bill 314 introduced by Rep. Steve Harshman. It came close to passing in the House (26-30). This next year we plan to write every Senate and House representative to encourage them to pass an inflation adjustment.

Now going on 13 years, the need is very apparent. The WREP board has met with Gov. Gordon, the WRS board and Rep. Harshman to get their support. We are asking all retirees to please contact your House and Senate legislators to support some kind of inflation adjustment in 2020.

December 20, 2019

Public News Service

On December 1, retired public employees in Wyoming saw a 12% increase in the cost of their health coverage, which is taken directly out of their monthly pension checks.

Retirees receive, on average, $1,600 in pension benefits a month, and Betty Jo Beardsley – executive director of the Wyoming Public Employee Association – worries that many might have to start making difficult decisions.

She says for a Wyoming retiree, a 12% reduction amounts to half a month’s worth of groceries and four tanks of gas.

“So, we’re hoping that we can find a way to offset that premium increase, to help them with the impact to their actual take-home pay from their pension check,” says Beardsley.

Beardsley notes the entire state could soon start to feel the impacts. According to the National Institute on Retirement Security, expenditures stemming from pensions in 2018 supported 5100 Wyoming jobs, and each dollar paid in benefits supported $1.22 in total economic activity.

Joe McCord, a retired state worker, says Wyoming lawmakers have a role to play to fix what could otherwise have been a gradual rise in health costs. One option before the Legislature is to approve a 4% inflation adjustment for retired public employees, which would be the first such adjustment in 12 years.

But McCord says that still wouldn’t cover the hike in health insurance costs.

“You know, there’s a lot of state employees and retirees that don’t make a lot of money,” says McCord. “They’re living on a very small amount of money. And it needs to be adjusted – that health insurance needs to work for the people.”

McCord says Wyoming lawmakers also could opt to join 33 other states that have expanded Medicaid coverage. It’s projected that move alone would bring over a billion federal tax dollars into the state over the next decade, and expand health coverage to 27,000 residents.

December 13, 2019

Casper Star-Tribune

In the early 1990s, a woman who was struggling entered my office. She had two little boys and an ex-husband who refused to pay child support. I sat her down, discussed her options for assistance and asked a question I asked many young women who entered my office: “What are you going to do for the rest of your life?” I asked her this question because my job wasn’t just to process food stamp requests or to make sure young families wouldn’t end up on the street — it was to mentor and guide young people to make sure they never needed assistance again.

As a retired benefits specialist for the Wyoming Department of Family Services (DFS), these types of stories are not uncommon. That woman with two little boys ended up using a Pell Grant provided by the government to go to college and, after graduating, she got a job working for a local church, making more than enough to provide for her young family.

I worked for DFS for almost twenty years, helping families throughout Wyoming when they fell on hard times. My coworkers and I shared the same goals because as a community we lift people up; we don’t leave them behind. Working for DFS brought me great joy because, for my entire professional career, all I wanted to do was mentor young women and make sure they didn’t make the same mistakes I did when I was younger. As a recovering alcoholic who has been sober for 46 years, I know that everyone has that drive inside of them to accomplish great things even when they think they can’t. As a benefits specialist, I found that drive in people and lifted them up when their challenges tried to bring them down.

When I retired thirteen years ago after years of service to my community, I was provided a pension. My pension is very modest. Some in the Legislature would like you to believe that all retirees move to Florida and sail to the Bahamas every weekend on their yachts. Like most Wyoming Retirement System retirees, I stayed right here in my community, where I volunteer with the local chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous and teach folks around the community genealogy through my church. I love Wyoming because this is my home.

Since I retired, each year it has become tougher to get by. In 2008, the Wyoming Legislature issued its last inflation adjustment for retired public employees. It has been a long 12 years since we have seen any relief. In that time, the price of groceries and healthcare has continued to increase and my modest pension benefit no longer covers all of the costs. Retirees’ health care deductibles are increasing and the cost of prescription drugs is skyrocketing. Many retirees like me aren’t able to keep up.

This coming legislative session, lawmakers should pass a 4 percent inflation adjustment for Wyoming’s retired public employees. Each and every one of us are pillars of our communities: we’re your kids’ little league baseball coaches, your neighbors, friends, family and the people sitting next to you at church on Sundays. We need this inflation adjustment or some of us will slip further into poverty, and be forced to rely on the various services I once worked to make sure no one would ever need.

It’s no secret that Americans are falling short when it comes to saving enough for retirement. But as a new report shows, many are disastrously unprepared — and that may point to flaws in the system.

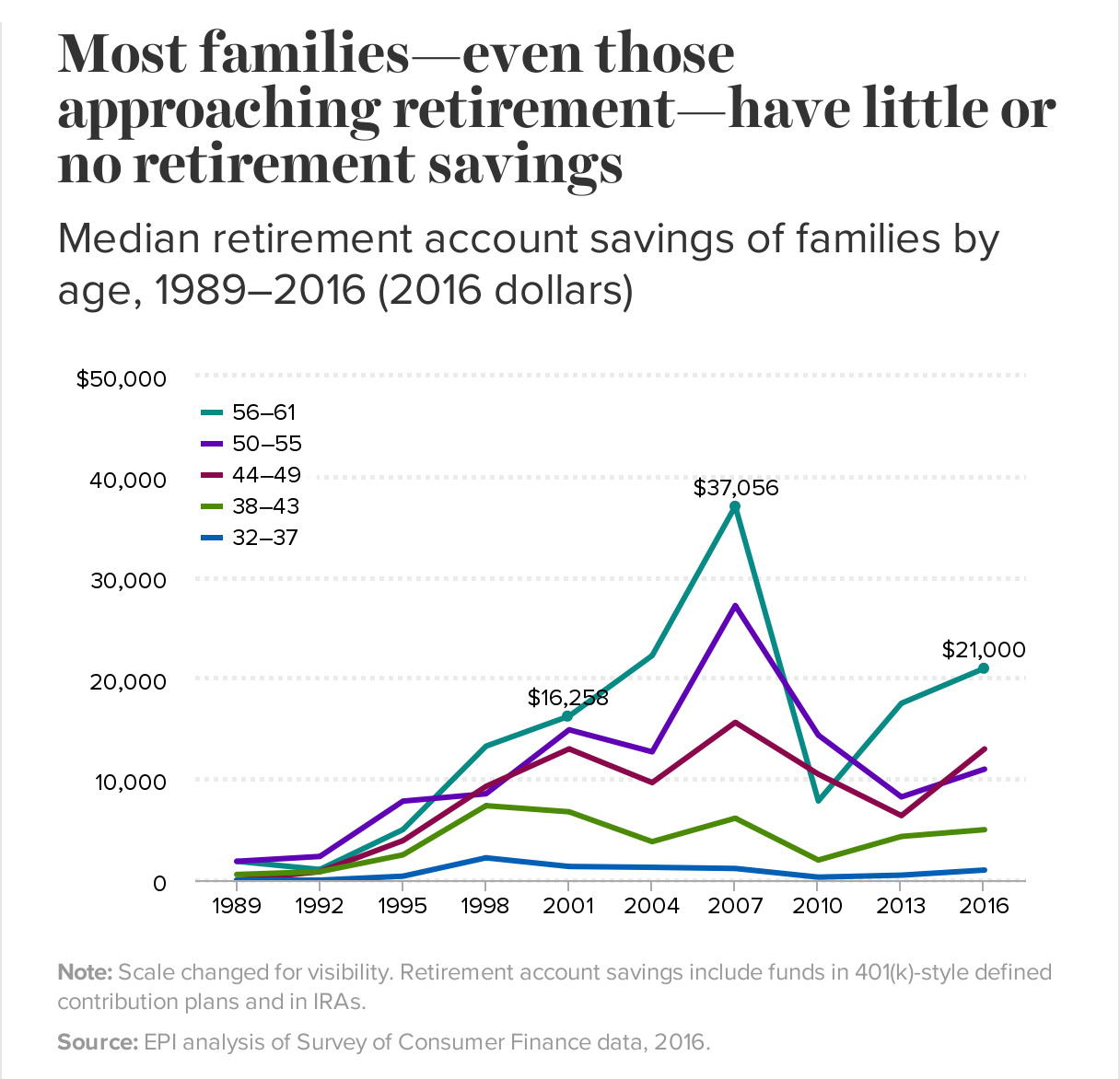

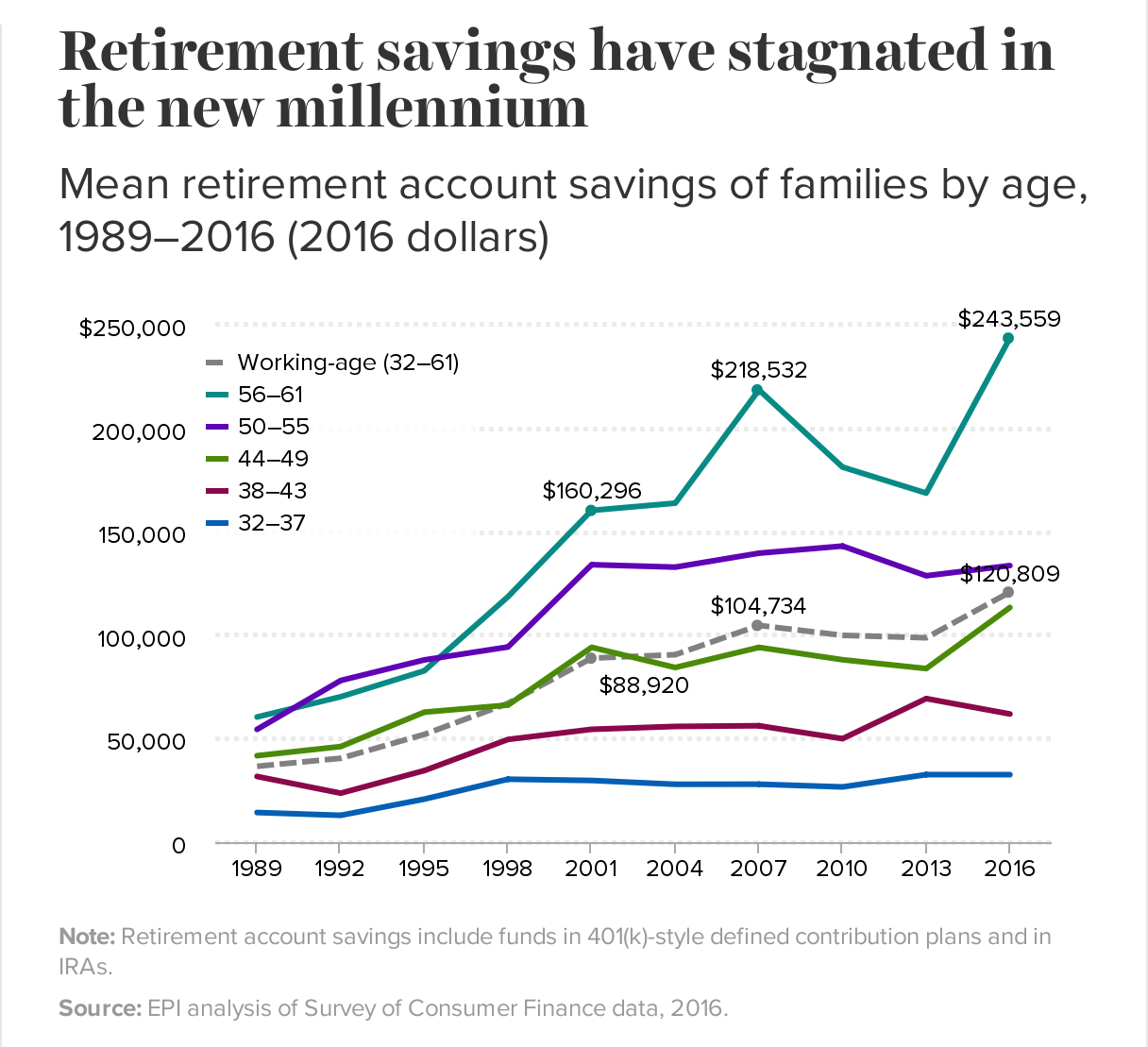

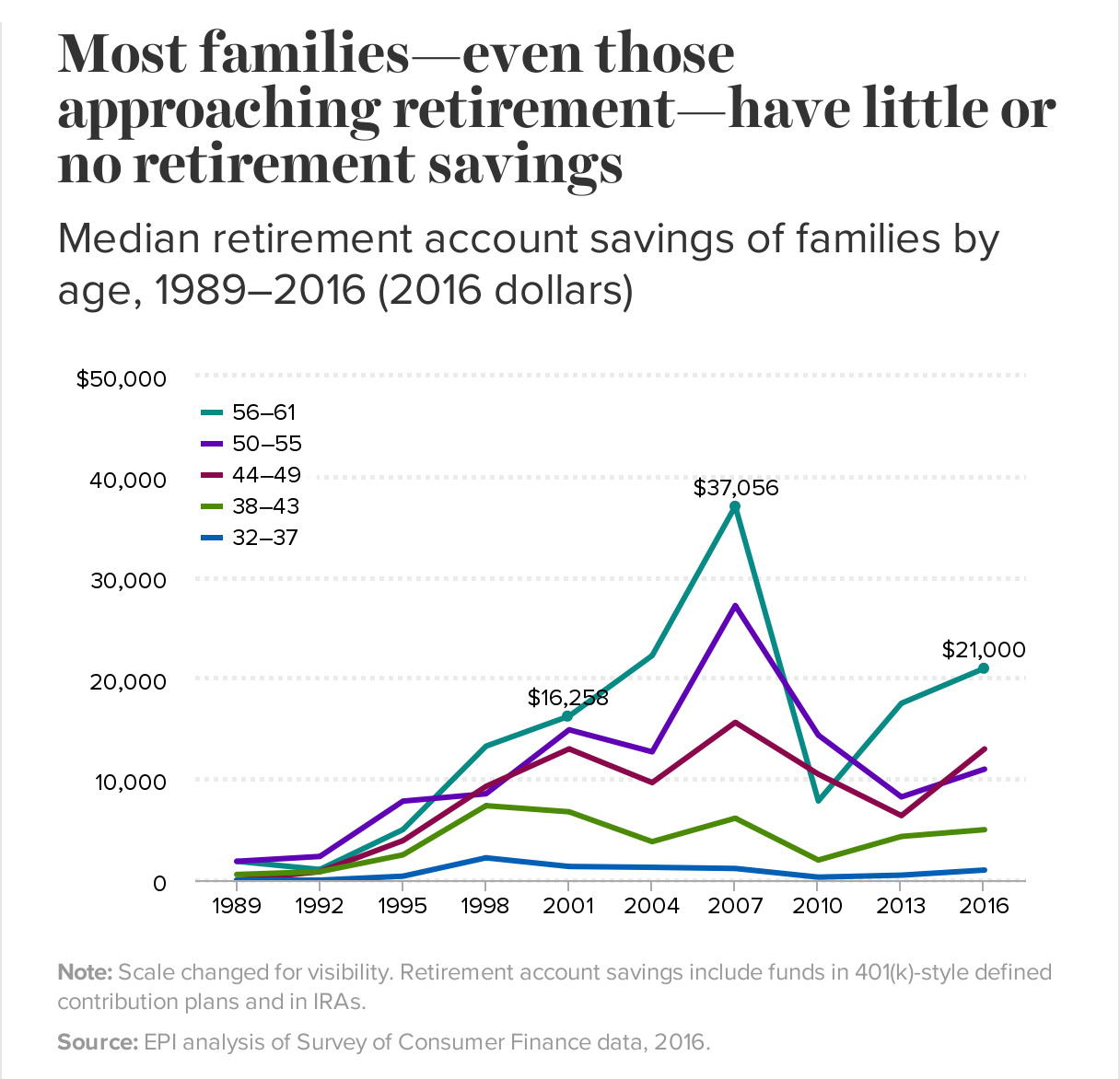

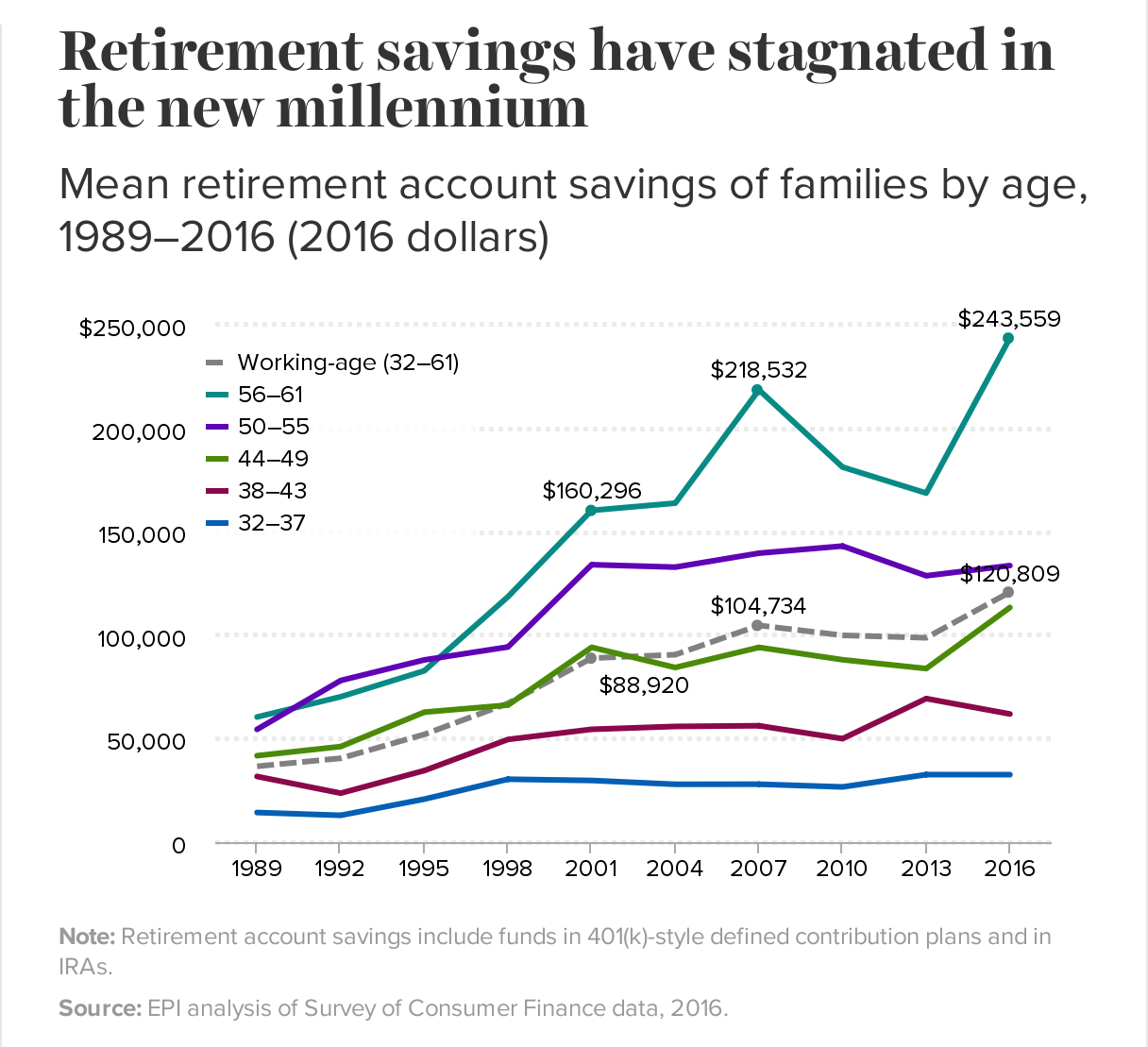

Progressive think tank the Economic Policy Institute found that Americans 56 to 61 had a median balance of $21,000 in their 401(k) accounts in 2016, which is the most up-to-date data on file. That total reflects almost 30 years of savings.

Younger generations do not fare much better. Older millennials (ages 32 to 37) have about $1,000 saved in their 401(k)s.

The problem is that while 401(k) plans are meant to supplement Social Security, the benefits distributed by the government agency are modest. Currently, the average Social Security retirement benefit is about $1,470 a month, or about $17,640 a year, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile, the typical American spent about $3,900 a month last year on basics such as food, housing, utilities, transportation and health care, according to the latest consumer spending data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retirement accounts, ranging from pensions to 401(k)s to individual retirement accounts, are expected to fill the gap.

But when it comes to 401(k)s, that’s not happening.

At least one economist says that the problem lies primarily with the plans, not with Americans’ savings habits. “The system is designed to make people feel bad about themselves — everyone privately thinks that they’re screwing up. And yet if everyone is screwing up, then it’s clearly a system flaw,” Monique Morrissey, economist at the Economic Policy Institute and author of the report, tells CNBC Make It.

Problems with the current system

As more and more American employers move away from offering pensions, 401(k)s and similarly structured retirement plans have risen in popularity. But the biggest problem with relying on 401(k) plans to supplement Social Security benefits is that many people simply don’t have access to employer-based retirement plans.

“The No. 1 problem is a coverage problem,” Morrissey says. Nearly 40 million private-sector employees do not have access to a retirement plan through their employer, according to a 2018 study by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Most people without any 401(k) savings are in that position because they don’t have access to a plan at work, often because their employer doesn’t have a plan at all, they’re part-time or they haven’t been at the company long enough to qualify.

Even if people are covered and participating in their retirement plan, Morrissey says “401(k) plans were not well designed to serve in lieu of a real pension.”

First, 401(k) plans can be difficult for employees to navigate, even with changes lawmakers have put in place to make it easier for consumers to get started. Last year, 65% of companies with more than 5,000 employees automatically enrolled workers in 401(k) plans at a small set deferral rate, according to data from Vanguard. Many times, these programs will start employees off at a 3% contribution rate and gradually increase it to 6%.

The system is designed to make people feel bad about themselves — everyone privately thinks that they’re screwing up. And yet if everyone is screwing up, then it’s clearly a system flaw.

Yet even though these auto-enroll programs get consumers started, the projections and assumptions that they need to make can be difficult to navigate. To determine how much you should invest to retire comfortably, you need to broadly estimate your lifetime earnings, as well as make some assumptions on what market returns will look like.

As Morrissey points out, small variations in those assumptions can make a huge difference. If you slightly tweak your expectations to be more pessimistic or more conservative, you could get results that specify you need to be saving close to half of your income.

If millennials want to retire at 65 and have enough to live off even half of their final salary in retirement, for example, they would need to save 40% of their income over the next 30 years if investments return less than 3%, according to recent academic research from Olivia S. Mitchell, a professor and executive director of Wharton’s Pension Research Council at the University of Pennsylvania.

That type of savings goal becomes “overwhelmingly impossible to do and people give up,” Morrissey says.

Additionally, 401(k) contributions are voluntary and you can tap your funds for a variety of purposes before retirement, a situation that makes these types of retirement savings accounts more “vulnerable” than traditional pension benefits to economic downturns.

How to boost your savings

For millennials, the good news is that it’s not too late to jump-start retirement savings. Juggling saving for retirement with covering rising day-to-day housing, health care and living expenses and working to wipe out existing debt can feel overwhelming, but it’s possible.

First, take some time to prioritize your financial goals. “Millennials will need to have a clear idea of what is most important to them in the long-term. Kids? House? Life experiences?” says Bart Brewer, a certified financial planner with California-based Global Financial Advisory Services. Trade-offs may need to happen, he adds.

It can also help to create a written monthly budget and carefully manage your credit. Young people need to be very careful about dramatically raising their standard of living, Brewer says. “It’s much harder to ratchet down after you’ve ratcheted up.”

And while they’re not perfect, it’s worth enrolling in your employer’s retirement plan if you’re eligible. Once you have your 401(k) account set up and your contributions flowing in, it’s important that you select how to invest your funds — otherwise your retirement money will essentially act like a savings account.

Millennials will need to have a clear idea of what is most important to them in the long-term.

Also, make sure to contribute enough to take advantage of any match your company may offer. Some companies offer to match the amount of money you put your 401(k), up to a certain point: If you put 5% of your salary into your 401(k), your employer may also contribute 5%, depending on the type of program. The median matching level is 4% among Vanguard 401(k) plans.

Last, you may need to consider working longer and waiting to claim Social Security until later. “Benefits from Social Security are 76% higher if you claim at age 70 versus 62, which can substitute for a lot of extra savings,” Mitchell says.

If you’re able, don’t retire, Mitchell says. “If you can keep working, do so. If you can’t work full-time, work part-time. Every little bit helps.”

A business-backed effort to get Oregon voters to reduce the costs of the state’s public pension system has quietly closed shop — at least for the 2020 election.

Backers had filed five potential ballot measures sponsored by two prominent Oregon political figures — former Democratic Gov. Ted Kulongoski and former Republican state Sen. Chris Telfer — that would revamp the benefits provided by the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System.

The Oregon Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) building in Tigard, Oregon, on Sunday, Jan. 6, 2019.

Bryan M. Vance/OPB

After earlier withdrawing three of the measures, supporters quietly dropped the last two the day before Thanksgiving.

Tim Nesbitt, the former Oregon AFL-CIO president who has worked with state business leaders on the issue, said actions taken during the last legislative session helped reduce the immediate air of crisis around a retirement system facing a $27 billion debt. In addition, he said, the booming stock market should also help hold down increases in pension costs in the near term.

As a result, he said, backers concluded it makes more sense to see how the finances of the system play out over the next several years — instead of trying to tackle the costs of the pension system during a 2020 general election dominated by a high-intensity presidential election.

How to solve the puzzle of PERS has been a hot topic in state politics repeatedly over the past two decades. Democratic Gov. Kate Brown last year defeated a Republican challenger, Knute Buehler, who wanted to make major cuts in PERS benefits. But she vowed to take action to reduce the rise in employer rates, which now average about 25% of payroll.

Brown signed a measure, Senate Bill 1049, earlier this year that makes some modest benefit reductions while also stretching out the time to pay off the unfunded pension liability.

Without the bill, pension costs were projected to rise to about 29% of payroll, costing public agencies another billion dollars over the two-year budget cycle, Nesbitt said.

Instead, employee rates are projected to stay about the same, particularly if this year’s stock market advances stick through the rest of the year. The pension system is heavily dependent on investment earnings, so the stronger the market, the more money generated to pay benefits.

“The legislation seems well-designed to avert another round of increases which would devastate budgets” for schools and other services in the next several years, Nesbitt said. “We should give the legislation time to see how it works.”

The withdrawal of the PERS initiatives pleased the public employee unions, which have bitterly opposed any reductions in worker benefits.

“I think it’s time for them to stop these corporate-backed attacks on hard-working public employees,” said Patty Wentz, a spokeswoman for the PERS Coalition, which represents several unions.

She argued that attempts to cut pensions only make it harder to attract and retain talented teachers, firefighters and other public employees. And she said that voters made it clear when they rejected Buehler’s gubernatorial candidacy that they weren’t interested in cutting pensions.

Nesbitt said his supporters could return in later years for another attempt at initiative reform. He noted that the Oregon Supreme Court is considering the constitutionality of the PERS measure signed by Brown this year. The court’s decision could roll back some or all of the benefit cut. And it will also provide more clarity on what benefit changes it is willing to accept.

The business-backed measures prevented a variety of approaches to reducing costs. They include shifting new workers to 401(k)-style retirement plans and diverting some contributions to existing public employee retiree investment accounts toward paying the costs of the main pension plans, which guarantee workers a set pension amount depending on their pay and years of service.

One other pension-related measure has been filed for the 2020 ballot. It’s sponsored by two former Republican state representatives — Julie Parrish of West Linn and Mark Johnson of Hood River — and Portland activist Kim Sordyl. Their measure would amend the state constitution to require future benefits for all public pensions to be paid without going into debt. The intent is to force public agencies to either lower their pension costs or to ensure they are paid without borrowing.

Parrish said she and other sponsors are still deciding whether to go ahead with the measure. She expressed confidence that they could collect enough signatures to qualify for the ballot but acknowledged the difficulty of raising enough money to conduct a fall election campaign against determined union opposition.

“We are committed to this concept,” she said. “The real question is are we going to roll the dice and get it done this [upcoming] year, or do we take the full two years going into the ’22 cycle.”